Army@Love: The Art of War was a comic book series produced by D.C. Vertigo Comics that satirised the Global War on Terror, which ran from November 2008 to March 2009 (Veitch & Erskine, 2008). Its premise is that the U.S. military, suffering from low public support in the face of an interminable war in the Middle East, begins to employ “unorthodox” marketing tactics to improve enlistment numbers. Essentially, the private sector is brought in to improve conscription and does so by creating the ultimate adrenaline-fueled experience for a generation raised on hardcore pornography and first-person-shooter games: The Hot Zone Club. You can look up exactly what they mean by that elsewhere. That side of things is not the focus today. Instead, I want to consider whether comics, with their mass accessibility and broad appeal, can actually push back against dominant media narratives.

This review will consider the Army@Love title in relation to Ono & Sloop’s (1995) proposed theory of vernacular rhetoric. Ono & Sloop argue that the value of vernacular forms lies in their capacity to present a challenge to dominant discourses, and this feels particularly pertinent where the high-stakes themes of global geopolitics and military intervention are concerned.

Post-millennial popular and colloquial media forms have become the focus of theoreticians exploring the visual culture of conflict. These include psychological operations leaflets (Clark & Christie, 2005), soldier-produced imagery (Kennedy, 2009) and even digital memes (Silvestri, 2016). These are all formats that have been historically side-lined or academically undervalued. The comic book format has suffered from this, having long been associated with ‘inconsequential gags’ and ‘reductive art’ (Soper, 2013, p. 8) despite titles such as ‘Wanda the War Girl’ (Chapman, 2011) and G. B Trudeau’s long-running ‘Doonesbury’ (Soper, 2013) playing a significant role in shaping public perceptions of armed conflicts in the past.

Ono & Sloop (1999, p. 529) outline three criteria for texts to be considered as a vernacular form of rhetoric: firstly, the text is readily accessible to ordinary audiences. Secondly, the text borrows from mainstream imagery and blends dominant motifs with transgressive elements. Finally, the text proposes rhetoric that is incompatible with existing governing structures and seeks to ‘undermine [existing] dominant logics’ entirely rather than simply point out their weaknesses or harmful elements.

In my opinion, Army@Love fulfils two of these three requirements; firstly, the comic book is an affordable and highly visual cultural artefact. The Army@Love series retailed at just $2.99 per issue at the time of publication. Comic book series rely less on allegorical figures as stand-ins for more complex ideas than single-panel formats. This lessens the need for prior political and/or historical knowledge to understand the story being told. They are, therefore, much more accessible to a broader range of social classes and literacies than dense historical texts requiring pre-existing cultural capital.

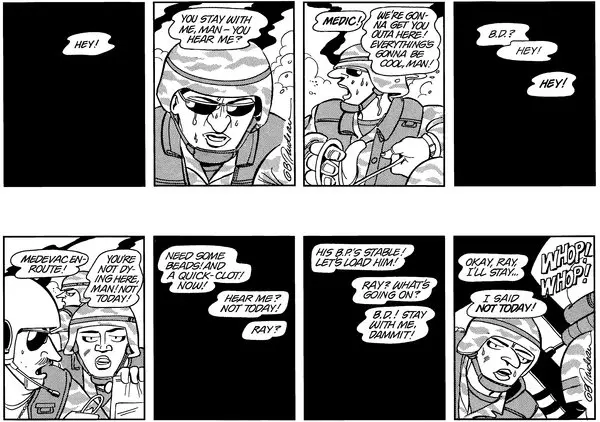

The serial format is also more nuanced than the newspaper single-frame panel titles usually associated with politically engaged cartooning. In this way, comic book series offer more opportunities for thorough character development and elicit a greater emotional investment from audiences. This capacity for narrative expansion heightens its ability to evolve from a throwaway entertainment product into a more potent rhetorical form.

In addition, the series borrows imagery from dominant forms and plays with intertextuality and juxtaposition. The visuals are never entirely resistant to dominant narratives, but instead, they selectively absorb motifs and redeploy them in new hybridised forms. This blend is referred to as ‘cultural syncretism’ (Smith, 2009, p.80), expressed as ‘pastiche’ (ibid.) that instrumentalizes universally recognised imagery in the service of subversion.

Cover of the October 2008 issue of ‘Army@Love: The Art of War’ comic book series. Published October 2008.

Pastiche takes advantage of recognisable tropes and uses them to challenge established conventions or expectations. The October 2008 issue of Army@Love’s cover illustration is a salient example. It features a bulletproof vest-clad and firearm-wielding Mona Lisa. This functions as a play on the series subtitle (‘The Art of War’) but also as a dig at the West’s self-identification as a civilising force in global conflicts. A serene and iconic portrait of the Renaissance contrasting with a backdrop of material destruction makes a point of our hypocrisy. The Anglo-American coalition positions itself as an example of an enlightened society while razing another to rubble, echoing the repeated media framing of our morally righteous Global War on Terror.

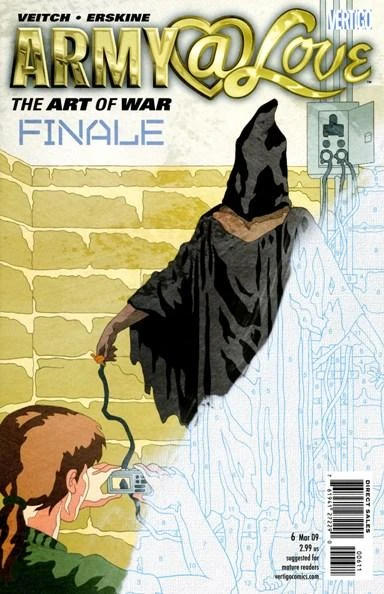

Cover of the final issue of the ‘Army@Love: The Art of War’ comic book series. They were published on 6 March 2009

Articulating ideas about asymmetrical warfare through a primarily visual medium allows the authors to make subjects visible and force audiences to witness acts that governments or institutions may have attempted to suppress (Mirzoeff, 2006). The cover image of the final issue shows the infamous picture of the ‘Hooded Man’ of Abu Ghraib prison. The bottom right-hand side is reduced to an outline drawing of the scene, which mimics a ‘paint by numbers’ activity, perhaps suggesting the officers conducting the torture were mindlessly following orders from higher in the chain of command. The illustration of a now-iconic image of suffering coincides with the banality and naivety of the paint-by-numbers format to provoke the audience to reconsider the ‘just war’ narrative it is being served (Peterson, 2018).

Finally, Ono & Sloop emphasise the need for these outlaw perspectives not just to aggravate but be entirely ‘incommensurable’ (1999, p. 528) with existing production, distribution, and governance structures. This final characteristic of vernacular practice could be seen to discount the accessibility and massive audience potential of popular culture in favour of a difficult-to-attain ideological purity. Their suspicion towards commercial outputs may be justified if consumers are assumed to be passive and disempowered receivers of texts. However, some theorists have argued that the consumption of popular culture also necessitates audience agency and productivity; they must first select what to engage with from the marketplace, then deconstruct the messaging involved, sometimes creating new fan-made products (Dienst, 2012; Jenkins, 2013).

According to Ono & Sloop’s definition, the comic book’s commercial nature compromises its ability to offer a “true” outlaw perspective in favour of outcomes that increase circulation numbers, leading to increased commercial success. Suppose the production of the cultural output remains inextricable from the requirement to generate income. In that case, its rhetorical content will likely have been exaggerated or degraded for shock value rather than with any persuasive political aim in mind. However, Ramazani (2022) argues that it is the moral and political responsibility of the media ecosystem to challenge and interrogate official narratives of war and makes no exception for formats that fall under the banner of mass entertainment. Given the storied history and increasing interwovenness of the military-industrial complex and entertainment corporations, this seems a more pragmatic and contemporary perspective.

So, whilst Ono & Sloop (1995) correctly encourage examining texts outside of traditional historical considerations, commercial popular culture forms such as comics should not be discounted as a site of meaning-making for the public. It is hard to qualify the real-world rhetorical efficacy of a title like Army@Love without performing some reception analysis. Still, Ono & Sloops’ emphasis on incommensurability as a condition of outlaw discourse risks disregarding the potential for (semi)vernacular forms such as comics to leverage the seductive and shocking qualities of entertainment to engage the civic imagination critically.

References

Chapman, J. (2011). Representation of female war-time bravery in Australia’s Wanda the War Girl. Australasian Journal of Popular Culture, 1(2), pp.153–163. doi:10.1386/ajpc.1.2.153_1.

Clark, A. M., & Christie, T. B. (2005). Ready... Ready... Drop! A Content Analysis of Coalition Leaflets Used in the Iraq War. Gazette (Leiden, Netherlands), 67(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/0016549205050128

Dienst, R. (2012). Still Life in Real Time. Duke University Press.

Jenkins, H. (2013). Textual poachers: television fans and participatory culture. New York; London: Routledge.

Kennedy, L. (2009) “Soldier photography: visualising the war in Iraq,” Review of International Studies. Cambridge University Press, 35(4), pp. 817–833. doi: 10.1017/S0260210509990209.

Ono, K.A. and Sloop, J.M. (1995). The critique of vernacular discourse. Communication Monographs, 62(1), pp.19–46. doi:10.1080/03637759509376346.

Ono, K.A. and Sloop, J.M. (1999). Critical rhetorics of controversy. Western Journal of Communication, 63(4), pp.526–538. doi:10.1080/10570319909374657.

Peterson, M. (2018). Was Iraq a just war? Depends when you ask. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/03/iraq-war-ethics/556448/.

Ramazani, V. (2022). Rhetoric, Fantasy, And the War on Terror. S.L.: Routledge.

Silvestri, L. (2016). Mortars and memes: Participating in pop culture from a war zone. Media, War & Conflict, 9(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635215611608

Smith, C. (2009). The YouTube War as Vernacular Visual Rhetoric. PhD Thesis.

Soper, K. (2013). The Comics Go to War. War, Literature, Art, [online] 25(1). Available at: https://www.wlajournal.com/wlaarchive/25_1/Soper.pdf [Accessed 7 October 2022].

Veitch, R., Erskine, G., and DC Vertigo Comics (2008). Army@Love: The Art of War. Army@Love Comic Book.

Veitch, R. Erskine, G., and DC Vertigo Comics (2008). October 2008 Issue Front Cover. Army@Love.

Veitch, R., Erskine, G., and DC Vertigo Comics (2009). Army@Love: The Art of War Finale Cover. Army@Love Comic Book.